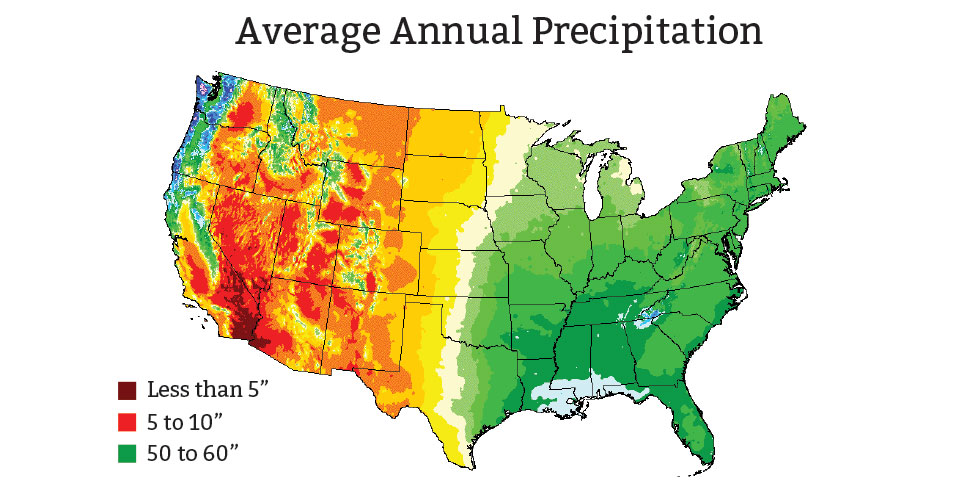

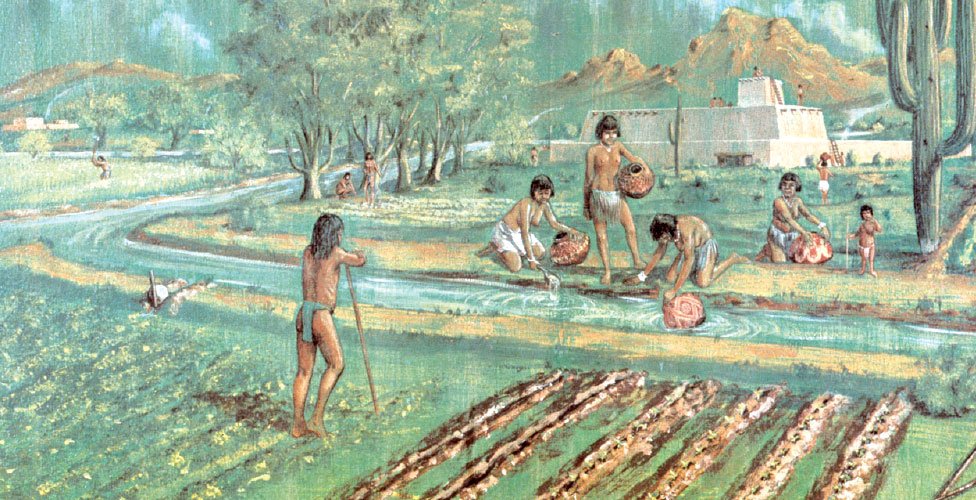

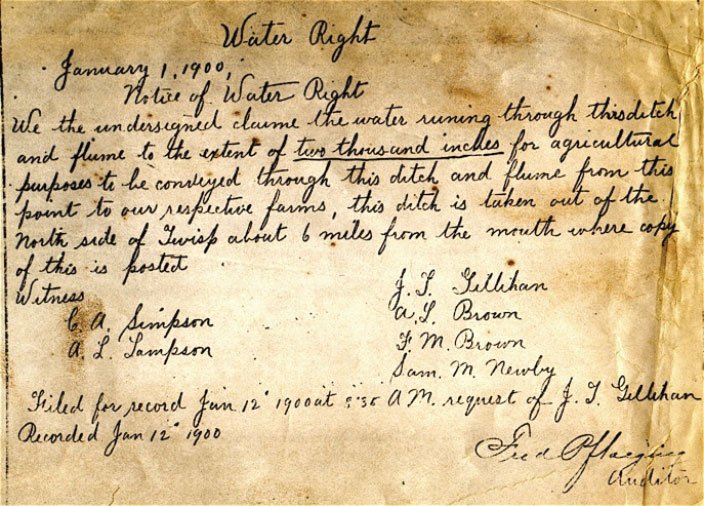

To settle the West, people first had to develop innovative ways to capture, manage and distribute limited water resources. Efforts to transform the desert of the American West into livable land began in prehistoric times. Between 450 and 1500 AD, the Hohokam built vast canal networks in the Salt River Valley in the area around modern-day Phoenix, Arizona. 300 miles of canals fed 256,000 acres where they grew crops like cotton, tobacco, maize, beans and squash. Families held claims to plots of land and those claims were passed down within the family. But the rights to use the water for irrigation belonged to the community. The water was allocated according to the amount of land each household cultivated.

Throughout history, people living in the West have had to develop systems for capturing, managing, and distributing water. Between 450 and 1500 AD, the Hohokam people built vast canal networks in the Salt River Valley in the area around modern-day Phoenix, Arizona. 300 miles of canals fed 256,000 acres of fields for growing crops like cotton, tobacco, maize, beans, and squash. Claims to plots of land were held by families, and they were passed down from parents to children. But the rights to use water for irrigation belonged to the community. The community allocated water to each household based on the amount of land they cultivated.

Over the years, other settlers developed their own systems for managing water. Some succeeded while others failed. But then in 1902, the federal government began large-scale projects that brought big changes to water management.

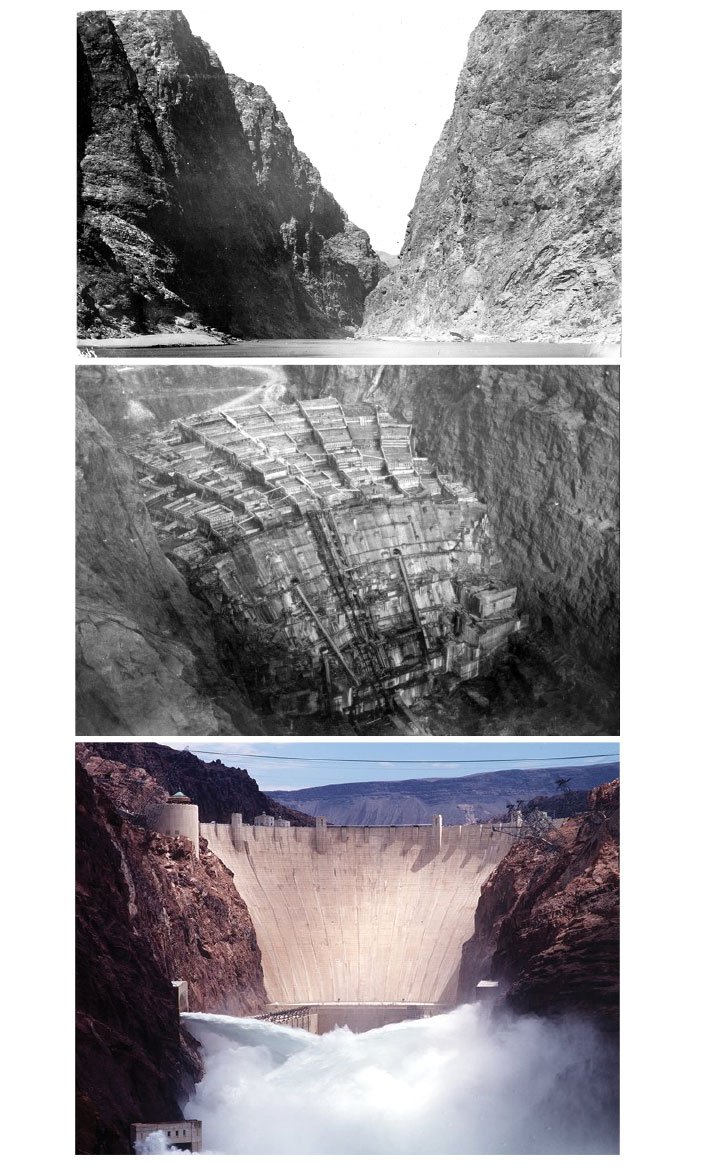

For many years, the federal government had been surveying Western lands. They considered the West an untapped resource, and they believed that transforming it into productive farmland and cities would help the nation prosper. The Reclamation Act of 1902 funded the building of “irrigation works for the storage, diversion and development of waters” in 20 western states. Over the decades that followed, massive networks of dams, reservoirs, canals, and pipelines were put in place to capture, hold, and distribute water. People moved westward, the population grew, and the region changed immensely.

When Hoover Dam was built in 1930, the nearby town of Las Vegas had just 5,165 residents. Now it’s a city of over 2 million. Similar growth took place in other western towns—Denver, Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix. Today most of the region’s 63 million residents live in cities, and the population continues grow by about 1 million each year.

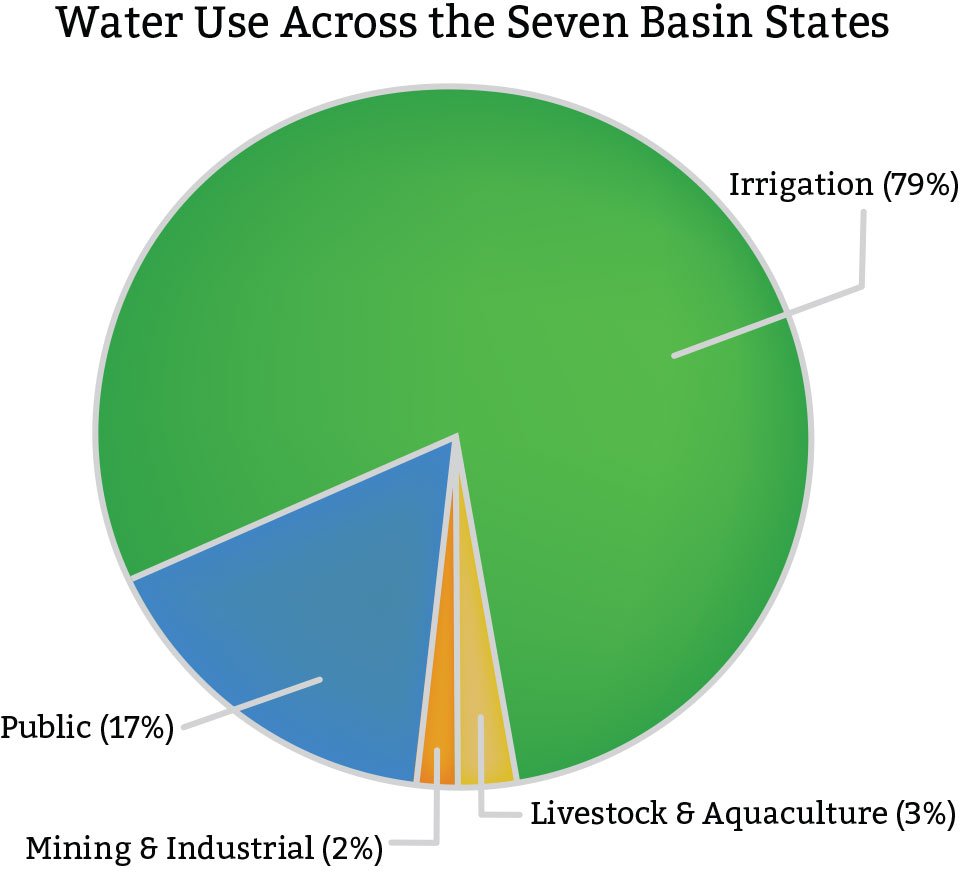

All of those residents, and the industries that employ them, use a lot of water. Water use in most western states is now nearly 3 times the national average. Water managers have the challenging task of distributing a limited supply of water to everyone who needs it.