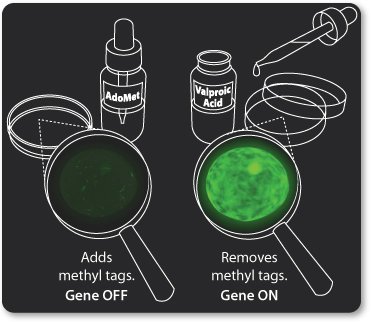

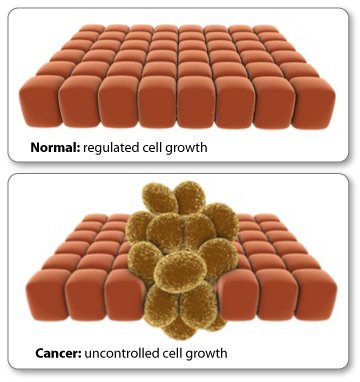

Signals from the outside world can work through the epigenome to change a cell's gene expression.

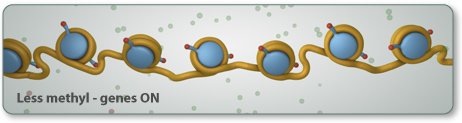

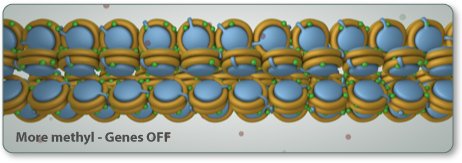

In the activity below, you act as the signal. As you turn the control knob, epigenetic tags come and go to change the shape of the gene.

Notice what happens to the mRNA and protein levels when you manipulate the epigenetic tags on the gene. Gene, mRNA, and protein production are linked. They change together.

For more information about transcription, translation, and the molecules of inheritance, visit Basic Genetics.