References

Baillie-Hamilton, P. F. (2002). Chemical toxins: a hypothesis to explain the global obesity epidemic. J Altern Complement Med, 8(2), 185-92.

Bergman, A., et al., Eds. (2012). State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals 2012: Summary for decision makers. A publication by the Inter-Organization Program for the Sound Management of Chemicals. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/78102/1/WHO_HSE_PHE_IHE_2013.1_eng.pdf (accessed 6/20/14).

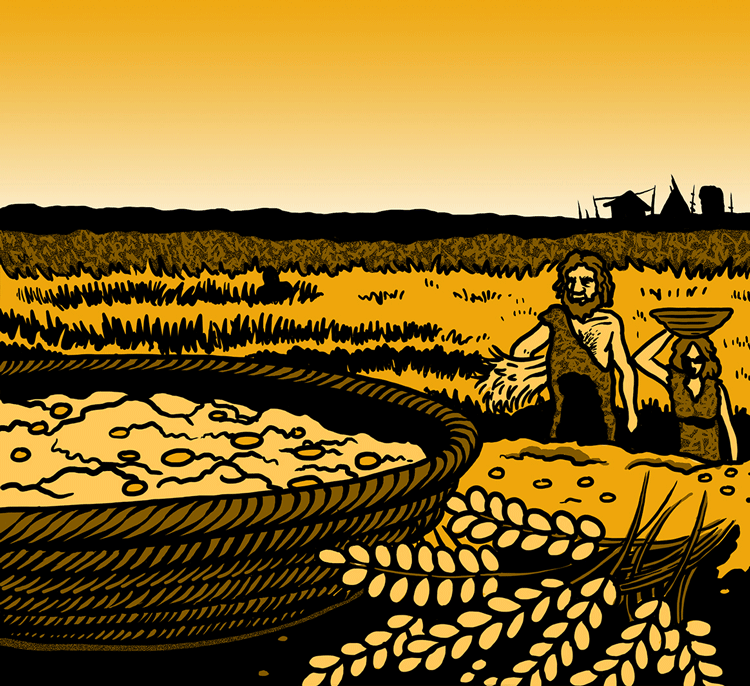

Bogucki, P. (1996). The spread of early farming in Europe. American Scientist, 84(3), 242-253.

Caballero, B. (2007). The global epidemic of obesity: an overview. Epidemiol Rev, 29(1), 1-5. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm012

Choquet, H. & Meyre, David. (2011). Genetics of obesity: what have we learned? Curr Genomics, 12(3), 169-79. doi: 10.2174/138920211795677895

Eaton, S. B. & Eaton, S. B. (2003). An evolutionary perspective on human physical activity: implications for health. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol, 136(1), 153-9.

Ganswisch, J. E. (2009). Epidemiological evidence for the links between sleep, circadian rhythms and metabolism. Obes Rev, 2, 37-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00663.x.

Gerbault, P., Liebert, A., Itan, Y., Powell, A., Currat, M., Burger, J., Swallow, D., & Thomas, M. (2011). Evolution of lactase persistence: an example of human niche construction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1566), 863-77.

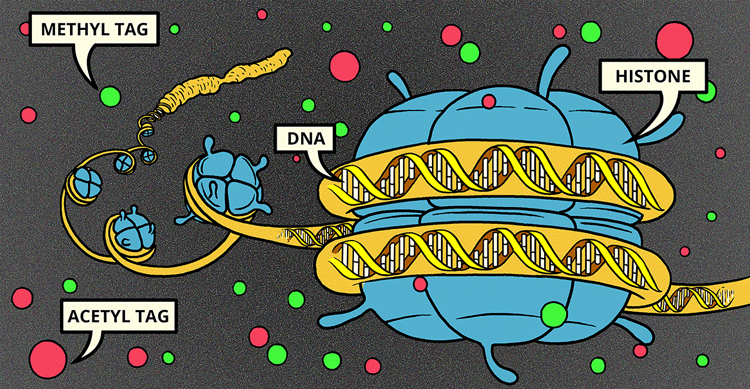

Gluckman, P. D. & Hanson, M. A. (2008). Developmental and epigenetic pathways to obesity: an evolutionary-developmental perspective. International Journal of Obesity, 32, S62-S71. doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.240

Holtcamp, W. (2012). Obesogens: An Environmental Link to Obesity. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120:a62-a68. (Updated 01 February 2012). Available: http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/120-a62/#r8 (accessed 6/18/14).

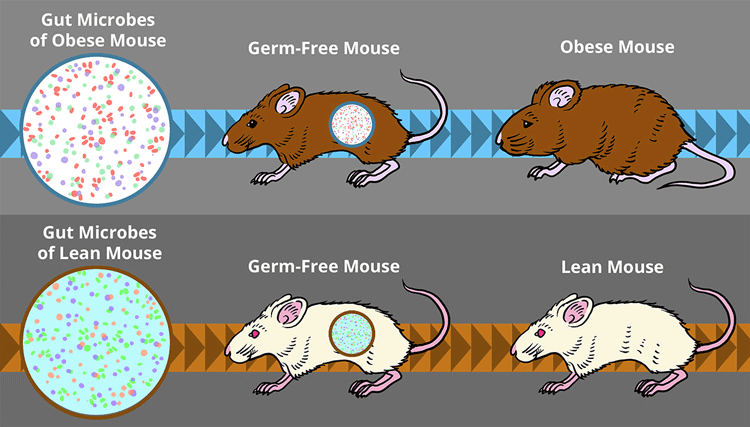

Kalliomaki, M., Collado, M. C., Salminen, S., & Isolauri, E. (2008). Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight. Am J Clin Nutr, 87(3), 534-8.

Kettunen, J., Silander, K., et al. (2010). European lactase persistence genotype shows evidence of association with increase in body mass index. Hum Mol Genet, 19(6), 1129-36.

Lillycrop, K. A. & Burdge, G. C. (2010). Epigenetic changes in early life and future risk of obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 35, 72-83. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.122

Maes H. H., Neale, M. C., & Eaves, L. J. (1997). Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet, 27(4), 325-51.

Newbold, R., Padilla-Banks, E., Jefferson, W. N., & Heindel, J. J. (2008). Effects of endocrine disruptors on obesity. International Journal of Andrology, 31(2), 201-208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00858.x

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kitt, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2014). Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 311(3), 806-814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732

Power, M. L. & Schulkin, J. The evolution of obesity. (Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). 302-03.

Rickard, I. J., & Lummaa, V. (2007). The predictive adaptive response and metabolic syndrome: challenges for the hypothesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 18(3), 94-9. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2007.02.004

Rogers, A. R. The Evidence for Evolution. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Shen, J., Obin, M. S., & Zhao, L. (2013). The gut microbiota, obesity and insulin resistance. Mol Aspects Med, 34(1), 39-58. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.11.001

Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Penev, V. & Van Cauter, E. (2004). Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med, 141(11), 846-50. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008

Stringer, C. (2003). Human evolution: Out of Ethiopia. Nature 423, 692-95. doi:10.1038/423692a

Tagiabue, A. & Elli M. (2013). The role of gut microbiota in human obesity: recent findings and future perspectives. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 23(3), 160-8. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.09.002

Tang-Peronard, J. L., Anderson, H. R., Hensen, T. K., & Heitman, B. L. (2011). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and obesity development in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 12(8), 622-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00871.x.

Vickers, M. H. Ikenasio, B. Al, Chan, K. Y., et al. Fetal programming of appetite and obesity. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 185(1-2), 73-79. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00634-7

Walley, A. J., Asher, J. E., & Froguel, P. (2009). The genetic contribution to non-syndromic human obesity. Nat Rev Genet, 10(7), 431-42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2594

Well, J. C. (2007). Flaws in the theory of predictive adaptive responses.

Trends Endocrinol Metab, 18(9), 331-7. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2007.07.006

Wells, J. C. (2012). The evolution of human adiposity and obesity: where did it all go wrong? Dis Model Mech, 5(5), 595-607. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009613

Wyce, C. A., Selman, C., Page, M. M. ,Coogan, A. N., & Hazlerigg, D. G. (2011). Circadian desynchrony and metabolic dysfunction; did light pollution make us fat? Med Hypotheses, 77(6), 1139-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.09.023

Excellent general reference:

Zinn, A. R. (2010). Unconventional wisdom about the obesity epidemic. Am J Med Sci, 340(6), 481-91.